You really should lock in your mortgage. Rates are historically low and they have to go up…eventually.

You really should lock in your mortgage. Rates are historically low and they have to go up…eventually.

Sound familiar? It may well be one of the costliest fallacies in today’s mortgage market. It’s kind of like saying stocks have to fall because the market is already up 200%. Or home prices must drop because they’re up 80% in just a decade.

That’s not how it works. In the real world, the past has little impact on where prices (or rates) will be a year or more from now. Rates in particular can keep trending in one direction far longer than the mass population ever imagines possible. The early 1900s saw two decades of rock-bottom rates. And then there was this little place called Japan, where in the late 1990s rates plunged—and despite 20 years of rebound predictions, have never rebounded.

The “norm” for rates often changes as markets evolve to new economic realities. And by the time people looking in the rear-view mirror realize there’s a “new normal,” we’re well into a whole new trend. That may be precisely what’s happening in today’s rate market.

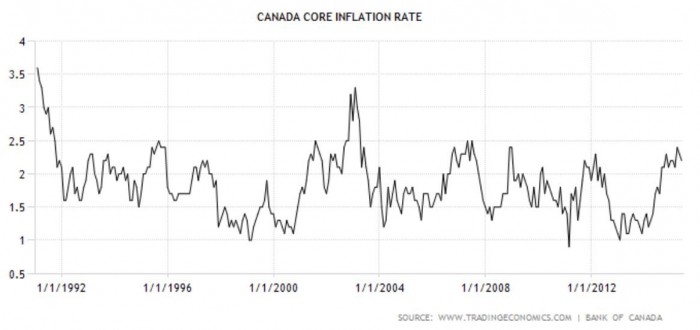

The #1 factor influencing interest rates long term is inflation. We know that for certain. We also know that, for over two decades, inflation has been a well-tamed animal. It’s hung around the BoC’s 2% target since the early ’90s when inflation targeting took hold.

And then there are inflation fundamentals. Those include downtrending economic growth, a near-immunity to commodity price spikes, disinflationary technological improvements and highly leveraged consumers. None of these realities support a persistent and rapid increase in the level of prices, and hence, rates.

Desjardins is one institution that appears to realize this. While other economists are forecasting a 2.35 percentage point surge in bond yields by 2018 (implying more than a two percentage point jump in 5-year fixed mortgage rates), Desjardins has quietly lowered its rate hike predictions. It’s now calling for just a 0.70 to 0.90 percentage point rise in discounted 5-year fixed mortgage rates over the next five years.

“Our sense is that competitive lending pressure will remain intense during the rate normalization process, which itself will be very slow by historical norms,” said Jimmy Jean, a Desjardins Senior Economist.

Of course it’s not the actual prediction you want to focus on. Exact forecasts don’t matter because they’re almost always wrong.

It’s more telling that economic trend watchers have begun slashing their forecasted rate increases. The once-“inevitable” 3 to 4 percentage point bounce back in rates has given way to talk of a much lower “new normal.” In terms of variable rates, the new norm is purportedly just over one point higher than today’s rates—i.e., a 2.00% overnight rate, say economists. (Again, don’t focus on the exact number.)

So let’s suppose that’s true for a moment.

A full-featured 5-year fixed will cost you roughly 2.54% today, and a variable rate, 2.05%. That’s a half point difference.

If the BoC starts lifting rates in two years and brings the overnight rate back to this theoretical “new normal” of 2.00%, then choosing a variable rate instead of a 5-year fixed would cost you $712 more interest per $100,000 of mortgage. That’s over 5 years, assuming equal payments.

Of course, the BoC could overshoot and lift rates more than 1.25 percentage points. But it could also cut rates beforehand, especially if recession fears mount.

So if a 2.00% overnight rate (4.10% prime rate) is the “expected risk” of going variable today, then historically speaking, that’s about as low a risk as variable-rate mortgage holders have ever faced. (The “potential risk” is higher, of course, so please stress-test your payments for a 2.00 to 2.50 percentage point increase.)

The point is simply this: Today’s well-qualified borrowers with stable income, liquidity and reasonable debt loads can afford to have more variable in their diets. And their mortgage doesn’t have to be all variable. Hybrid mortgages let you put as little as 1/4, 1/3 or 1/2 of your mortgage in a variable rate—if you so choose.

A floating rate component provides guaranteed interest savings up front, a lower penalty than many 5-year fixed mortgages, and the chance to participate in further BoC rate drops (even if banks don’t pass along every rate cut in full). Despite unusually low rates, a variable still offers a reasonable risk/reward ratio, given the economy’s long-term prognosis. If you’re a financially stable borrower, don’t let the “rates must go up” crowd dissuade you from considering one.

log in

log in

5 Comments

The hybrid mortgage seems like a good option for those (like me) who are still a little risk shy, but who want to participate in lower rates. Any idea which combination of fixed/variable in a hybrid mortgage is the most popular?

Hi JS,

“50/50” hybrids are the most popular — i.e., half 5yr fixed and half 5yr variable.

Going variable has served me well so far. It’s not for everyone though – for most I think the hardest part is ignoring the noise that’s out there

Never heard of hybrid mortgages. Are they available through all lenders? Thanks

Hi Chrissy,

No, they’re not. Only a minority of lenders offer competitive hybrids mortgages. The best options are generally available from the major banks and a few credit unions. The lowest hybrid rates are typically found through mortgage brokers, unless you’re well qualified, can negotiate and have a good lender rep in your corner.